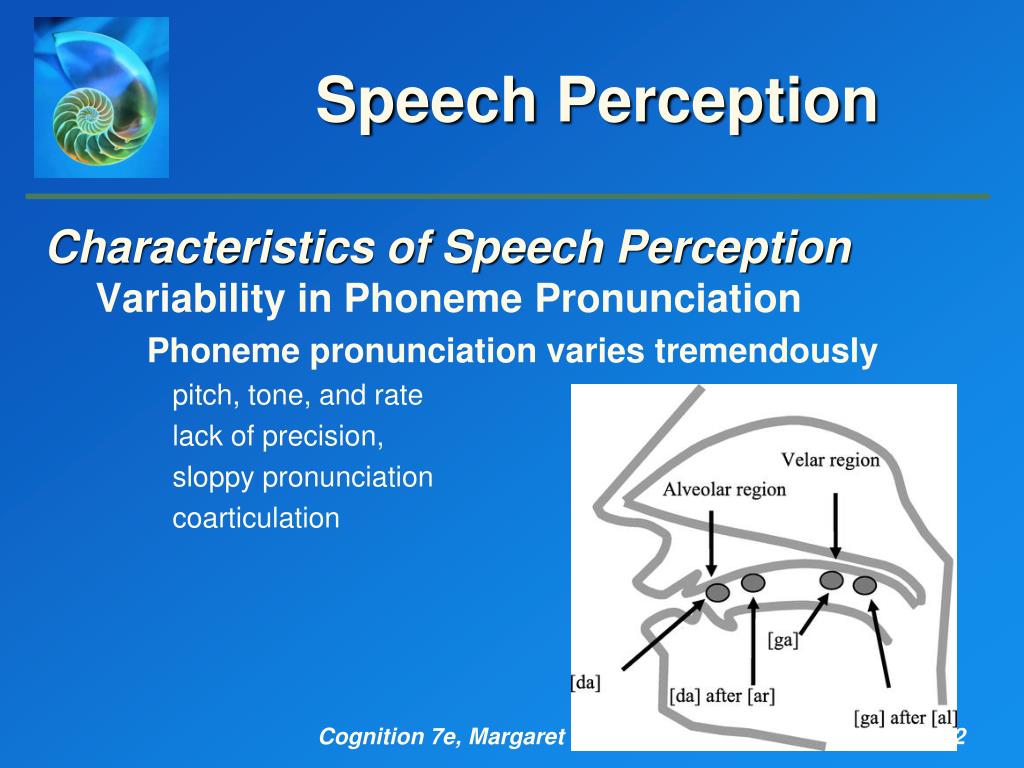

These data, indicating that there is not an immutable loss of phonetic abilities for non-native units ( 32), did not refute the selectionist position. Adult performance on non-native contrasts could be increased by a number of factors: ( i) the use of techniques that minimize the effects of memory ( 33, 34), ( ii) extensive training ( 35, 36), and ( iii) the use of contrasts, such as Zulu clicks, that are not related to native-language categories ( 37, 38). Modifications regarding the extent to which listeners “lost” the ability to discriminate non-native phonetic units were quick to follow ( 32). This ran counter to two prevailing principles at the time: ( i) the view that phonetic units were prespecified in infants, and ( ii) the view that language evolved in humans without continuity with lower species. On this view, particular auditory features were exploited in the evolution of the sound system used in language ( 19, 26, 27). Second, in the evolution of language, acoustic differences detected by the auditory perceptual processing mechanism strongly influenced the selection of phonetic units used in language. Differentiating the units of speech did not imply a priori knowledge of the phonetic units themselves, merely the capacity to detect differences between them, which was constrained in an interesting way ( 18, 19, 25, 27). First, infants' parsing of the phonetic units at birth was a discriminative capacity that could be accounted for by a general auditory processing mechanism, rather than one that evolved specifically for speech. Two conclusions were drawn from the initial comparative work ( 26).

The goal of this paper is to illustrate the recent work and offer six principles that shape the new perspective.

The new view reinterprets the critical period for language and helps explain certain paradoxes-why infants, for example, with their immature cognitive systems, far surpass adults in acquiring a new language. The results lead to a new view of language acquisition, one that accounts for both the initial state of linguistic knowledge in infants and infants' extraordinary ability to learn simply by listening to ambient language. The learning strategies-demonstrating pattern perception, as well as statistical (probabilistic and distributional) computational skills-are not predicted by historical theories. Studies of infants across languages and cultures have provided valuable information about the initial state of the mechanisms underlying language, and more recently, have revealed infants' unexpected learning strategies. The last half of the 20th century has produced a revolution in our understanding of language and its acquisition.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)